World War II

3 December 1996-Sixteen men who served in the Japanese Army were barred from ever entering the United States. They were the first Japanese placed on the Government's ''watch list'' since it was established in 1979 to keep out people who engaged in persecution on behalf of Nazi Germany or its allies.

Some of the barred Japanese veterans were members of Unit 731, an army detachment in Manchuria that conducted frequently lethal pseudo-medical experiments on thousands of non-volunteer prisoners of war and civilians. The other men are suspected of setting up and operating the Japanese Army's ''comfort women stations,'' where tens of thousands of women - many teenagers - were forced to have sexual relations with Japanese servicemen.

As well, several were involved in the reprisals against Chinese civilians who aided the Doolittle Raiders and paid a terrible price for helping the Raiders. In retaliation, Japan launched a three-month ground and air assault that included biological warfare agents unleashed on entire towns. Focused on areas in Zhejiang province (then Chekiang) where most of the US airmen had landed, the devastation was grim. Nationalist Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek sent a cable to the USA reporting that “Japanese troops slaughtered every man, woman and child in these areas.” His government estimated that up to 250,000 Chinese died.

Three of the captured Doolittle Raiders were executed. On 28 Aug 1942, Raiders Hallmark, Farrow, and Spatz were given a "trial" by Japanese officers, although they were never told the charges against them. On 14 Oct. 1942, Hallmark, Farrow, and Spatz were advised they were to be executed the next day. At 4:30 p.m. on 15 Oct. 1942 the three Americans were brought by truck to Public Cemetery No. 1 outside Shanghai. In accordance with proper ceremonial procedures of the Japanese military, they were then shot. Shown below is Robert Hite, who endured 3+ years in captivity, and passed away in 2015 at age 95.

7 March 1945-The bridge at Remagen, about fifteen miles south of Bonn, the Ludendorff Bridge crossed the Rhine River and was named after General Erich Ludendorff, Germany’s military leader during the latter half of World War I. The railroad bridge had been built—primarily by Russian prisoners of war—from 1916-1919 and had a span of 1,200 feet.

Just as the morning fog lifted on 7 March, Lt. Col. Leonard Engeman, heading a task force of the US Army 9th Armored Division’s 14th Tank Battalion and 27th Armored Infantry Battalion, was stunned to look through his binoculars and see the bridge still intact, with German vehicles still rumbling across it. Engeman dispatched Lt. Karl Timmermann (who was born in Frankfurt, Germany in 1921)with advance forces, including some new M26 Pershing tanks, to seize the bridge. He ordered: “Go down into the town. Get through it as quickly as possible and reach the bridge. The tanks will lead. The infantry will follow on foot. Their half-tracks will bring up the rear. Let’s make it snappy.”

Lt. Timmermann’s men approached the bridge at 3:15 p.m. with an increasing sense of urgency. German engineers blew a charge near the west span, damaging it and making it temporarily impassable for tanks. Timmermann nevertheless rushed the bridge with his infantry. The Germans tried to blow the central span, but the charges failed to detonate. Finally another charge blew and the bridge seemed to rise in the air—before settling back down on its original structure. In their haste, the German engineers had placed a detonator improperly—and those Russian prisoners of war had built the bridge too well!

Sergeant Alexander A. Drabik was given credit as the first American to cross the bridge to the east bank of the Rhine. There was hard fighting to follow as the Americans cleared the railroad tunneland secured the ridge overlooking the crossing. And although the Americans were able to make some quick repairs to the damaged bridge, allowing troops and vehicles to cross, it lasted only ten days longer before collapsing under pressures of traffic and German air attack before collapsing for good on 17 March.

The unexpected prize at Remagen forced the Allies to shift their strategy for invading central Germany, and more time would pass before they broke out from their new bridgehead. The crossing of the Rhine at Remagen, however, marked a decisive moment heralding the impending collapse of Germany.

The Great Escape

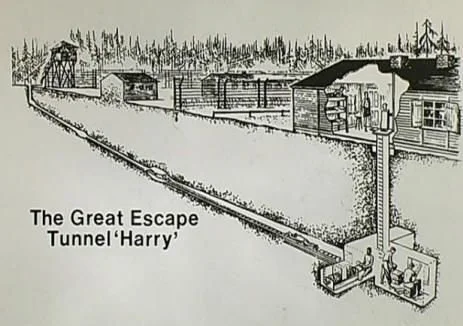

The mass escape of 76 Allied airmen from a Nazi POW camp in March 1944 remains one of history’s most famous prison breaks. Although the German Luftwaffe designed the Stalag Luft III camp to be escape-proof, the audacious, real-life prison break immortalized in the 1963 movie, "The Great Escape", proved otherwise.

When the Nazis built the maximum-security camp 100 miles southeast of Berlin to house Allied aviators captured in World War II—many of whom had made previous escapes—they took elaborate measures to prevent tunneling, such as raising prisoners’ huts off the ground and burying microphones nine feet underground along the camp’s perimeter fencing. In addition, the camp was built atop yellow sand that would be tough to tunnel through and difficult to conceal by anyone who tried. All of those German efforts were proven moot, however, when on the night of 23/24 March 1944, 76 Allied POW's escaped through the tunnel, "Harry", into the German countryside.

A Grossfahndung (nationwide alert) was declared with all forces, from the Gestapo through to the local police, tasked to locate the men. Over the coming days, all but three of those who escaped were recaptured, beaten down by the extreme cold and challenges of finding themselves adrift in enemy territory. A number of those with forged papers had intended to make swift headway by rail, but in the darkness, many had struggled to find the local station. Some simply pointed their compasses toward the nearest neutral country and began a futile trek through the frozen wastes.

Kommandant von Lindeiner was removed from duty and subsequently court-martialed for gross incompetence, though playing on his mental fragility the experienced military veteran managed to escape with only a token sentence - he would be later wounded defending Berlin, but survived the war. He was replaced by Oberst (Colonel) Braune to whom fell one of the grimmest yet memorable tasks of World War II.

On the morning of 6 April, Group Captain Herbert Massey, RAF, The senior allied officer, was summoned before the new Kommandant. Through an interpreter, the German Officer conveyed the somber news that forty-seven of those involved in the break-out had been “shot while trying to escape.” When repeatedly pressed by the shocked Massey on how many of the escapees had only been wounded, Braune reluctantly confirmed, “None.”

Bataan Death March

9 April 1942-The U.S. surrender of the Bataan Peninsula on the main Philippine island of Luzon to the Japanese during World War II, the approximately 75,000 Filipino and American troops on Bataan were forced to make an arduous 65-mile march to prison camps. The marchers made the trek in intense heat and were subjected to harsh treatment by Japanese guards. Thousands perished in what became known as the Bataan Death March.

The day after Japan bombed the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, on December 7, 1941, the Japanese invasion of the Philippines began. Within a month, the Japanese had captured Manila, the capital of the Philippines, and the American and Filipino defenders of Luzon (the island on which Manila is located) were forced to retreat to the Bataan Peninsula. For the next three months, the combined U.S.-Filipino army held out despite a lack of naval and air support. Finally, on April 9, with his forces crippled by starvation and disease, U.S. General Edward King Jr. surrendered his approximately 75,000 troops at Bataan.

The surrendered Filipinos and Americans soon were rounded up by the Japanese and forced to march some 65 miles from Mariveles, on the southern end of the Bataan Peninsula, to San Fernando. The men were divided into groups of approximately 100, and the march typically took each group around five days to complete. The exact figures are unknown, but it is believed that thousands of troops died because of the brutality of their captors, who starved and beat the marchers, and bayoneted those too weak to walk. Survivors were taken by rail from San Fernando to prisoner-of-war camps, where thousands more died from disease, mistreatment and starvation.

America avenged its defeat in the Philippines with the invasion of the island of Leyte in October 1944. General Douglas MacArthur, who in 1942 had famously promised to return to the Philippines, made good on his word. In February 1945, U.S.-Filipino forces recaptured the Bataan Peninsula, and Manila was liberated in early March.

After the war, an American military tribunal tried Lieutenant General Homma Masaharu, commander of the Japanese invasion forces in the Philippines. He was held responsible for the death march, a war crime, and was executed by firing squad on April 3, 1946.

Raid on Japan

Following the Raid on Japan by Doolittles Raiders on 18 April 1942, the crews of two planes remained unaccounted for. On 15 August 1942, it was learned from the Swiss consulate general in Shanghai that the Japanese had eight American flyers at police headquarters in that city. On 19 Oct. 1942, the Japanese broadcast that they had tried two crews of the Tokyo Raid and sentenced them to death. No names or facts were given.

A War Crimes Trial in Shanghai that opened in February 1946 uncovered the details. The court tried four Japanese officers for mistreatment of the eight POWs of the Tokyo Raid. In addition to being tortured, these men contracted dysentery and beri-beri as a result of the deplorable conditions under which they were confined.

On Aug. 28, 1942, the eight were given a "trial" by Japanese officers, although they were never told the charges against them. On Oct. 14, 1942, Hallmark, Farrow and Spatz were advised they were to be executed. The next day the Japanese brought them to Public Cemetery No. 1 outside Shanghai. In accordance with proper ceremonial procedures of the Japanese military, they were then shot.

The other five men (Meder, Nielsen, Hite, Barr and DeShazer) remained in solitary confinement on a starvation diet, their health rapidly deteriorating. In April 1943, they were moved to Nanking and on Dec. 1, 1943, Meder died. The other four men began to receive a slight improvement in their treatment and by sheer determination and the comfort they received from a lone copy of the Bible, they survived to August 1945 when they were freed.

What also is of mention, is the estimated 250,000 Chinese killed by the Japanese in reprisal for the assistance given by the Chinese for assisting the Doolittle crews who had ditched their aircraft in China, or right offshore.

The four Japanese officers tried for their war crimes against the eight Tokyo Raiders were found guilty. Three were sentenced to hard labor for five years and the fourth to a nine-year sentence.

In a photograph (below) found after Japan's surrender in 1945, Lt. Robert L. Hite, copilot of crew 16, is led blindfolded from a Japanese transport aircraft after his B-25 crash landed in a China after bombing Nagoya and he was captured. He was imprisoned for 40 months, but survived the war.

500 Yards

Veteran Sgt Major Robert Blatnik falls down on his knees in the sand of Omaha Beach. Back at the Beach over 70 years later where he came ashore on D-Day 6th June 1944 with the 1st Infantry Division.

Blatnik was 93 when he returned in 2013 to Omaha Beach stopping at the exact spot ( in the photo) where he landed on June 6, 1944

“Oh dear Father thank you for having saved my life,” he said as he got down on his hands and knees on the hallowed ground.

He commanded 901 men. Head count 24 hours later and about 500 yards inland, they had 387 men left alive. 500 yards.

Blatnik, who served under Gen. George S. Patton, in the 1st Infantry Division, nicknamed "Big Red One," said his experience helped keep him alive.

"I knew that the main thing to do was to get off the beach,” he said. “Some of the men wanted to dig in. When you're on a beach the main thing to do is confront the enemy. You can't dig in during something like that; you've go to get the hell off the beach. If you try to dig in you're lost, so I tried to keep my men moving forward."

D-Day — Normandy Landings

June 6, 1944. This date ought to be etched into the mind of every American. 160,000 troops crossed the English channel into France that day, storming beaches, scaling cliffs, leaping out of airplanes... the cost was steep. Over 4,000 Allied service members were lost, and in total there were about 10,000 friendly casualties. All in one day. It's almost impossible to fathom that kind of loss.

These men put everything on the line in the name of liberty and freedom against Axis tyranny. They weren't superheroes, they were just ordinary people asked to do an extraordinary, unimaginable task. And they did it.

Events like these feel like the happened in the distant past, but it hasn't been very long at all. Well over a couple thousand of these men are still alive today, and no doubt the memory of D-Day is alive and well with them. It's up to us to remember the sacrifices they made, to understand what they fought for, and to teach all of these things to the next generation.